Forgotten but not Gone

People are jailed for unpaid court debts tens of thousands of times each year

September 13th, 2023

Debtors’ prisons were once a central feature of the American legal system—so much so that even sitting supreme court justices could find themselves locked up for bad debts.1 Widely reviled—John Stuart Mill called them “barbarous expedients of a rude age, repugnant to justice as well as humanity”2—debtors’ prisons were outlawed in nearly every American state by the mid-1800s.3 Nevertheless, over the last decade, reports have emerged of people going to jail for unpaid debts in Ferguson, Missouri; Corinth, Mississippi; Jackson, Mississippi; and other cities and states.

What these debtors had failed to pay, however, was not commercial loans but rather court debts: fines, fees, restitution, and other “legal financial obligations.” Frequently, these debts were incurred for minor offenses in cases before municipal courts, the low-level courts that handle—often with very limited oversight—the traffic and other petty offenses making up the bulk of the judiciary’s caseload. Because these court debtors were scattered across the justice system and rarely subject to systematic tracking, little was known about them. There were no national—or even state-level4—statistics describing who these court debtors were, how much debt they owed, or how long they spent in jail.

In the absence of a clear picture of debt imprisonment, we set out in 2018 on a first-of-its-kind data integration effort to answer the most basic question of all: how many people are being jailed for unpaid court debts?

Finding the Data

The data needed to understand debt imprisonment were spread across the justice system. To get them, we filed hundreds of public records requests with county jails across the country seeking booking records that would allow us to identify individuals who had been jailed for unpaid court debts. This was a difficult task. Many jails did not have the data we needed. Others had the data, but found it difficult to extract from their records management systems, in some cases requesting hundreds or thousands of dollars—in one instance, $110,211.90—to do so. Most jails simply never responded to our repeated requests.

Ultimately, we collected data from 100 counties in five states—most in Texas

and Wisconsin—as well as state-wide data in two additional states, totalling

more than 4 million individual jail booking records. The data came in a huge

variety of formats: plain text files, CSVs, Excel spreadsheets, Word documents,

databases, and even PDFs of plain text files. To cope with this variety, we

made use of a variety of tools like Tabula and

pdftotext, as well as

developing our own tools to extract data from specific jail log formats, like

Odyssey and

NET Data. Once the data had

been extracted into a format that could easily be manipulated in R, we

developed a

data cleaning pipeline to:

- Classify the raw data,

- Parse the classified data into a standard format,

- Deduplicate rows corresponding to the same individual and separate distinct charges corresponding to the same jail stay,

- Standardize the data to remove clerical errors and misparsed data entries, and

- Impute missing data such as age and ethnicity where possible.

All of the data we collected and cleaned is freely available online.

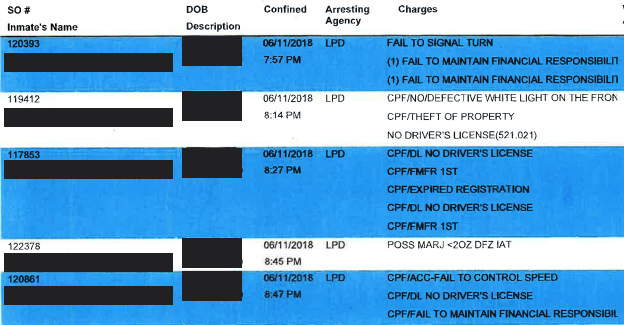

Defining “Failure to Pay”

The key challenge in this process was identifying which jail stays actually corresponded to court debtors. Jail bookings usually involve multiple charges. If one of those charges is for a serious jailable offense, even if the individual in question was also jailed for unpaid court debts, they would likely have been jailed anyway. To identify court debtors, we looked for individuals who were jailed for court-debt–related charges only. However, court-debt–related charges are often recorded in unclear ways or not recorded at all, and we had to learn the jargon that would identify them jurisdiction by jurisdiction. To ensure that our counts were appropriately conservative, we tried to code charges that were clearly failure-to-pay (FTP) related—for instance, charges actually mentioning “failure to pay” or “FTP,” charges where the individual had “laid out” some portion of their fines, charges corresponding to a capias pro fine (CPF) warrant in Texas, or charges coming from a municipal court in Wisconsin.5 Then, we counted the people who had been jailed only on charges related to failure to pay.

Counting Court Debtors

Using this data, we were able to estimate the number of people jailed for failure to pay in Texas and Wisconsin, between roughly 2005 and 2018. The month-by-month booking rates are shown below.

In both states, based on the counties that gave us data, the annualized rate is around 1,500 bookings per million residents. The dashed red reference line shows the per capita arrest rates in those states for burglary, which is substantially lower. Assuming these rates are representative of the states as a whole, that comes to roughly 38,000 jailings for unpaid court debt in Texas each year, and another 4,000 in Wisconsin. These estimates involve considerable uncertainty, since this assumption is unlikely to be true—the counties that gave us data are not random and differ from the states as wholes in observable ways—but seem unlikely to be off by an order of magnitude.6

Most of these jailings were short. In both Texas and Wisconsin, the median jail stay was a day. The average stay was longer—around two days in Texas and around six days in Wisconsin—reflecting the fact that a small number of individuals were jailed for much longer periods of time.

Most of the jailings also stemmed from relatively petty offenses. In Texas and Wisconsin, the majority of jailings were for traffic offenses (64%), and large numbers of jailings were for other minor offenses like public intoxication (7%), possession of marijuana and other petty drug offenses (5%), minor theft (4%), disorderly conduct (1.7%), and truancy (1.7%). While very few counties provided any information on the amount of court debt owed, warrant data from the state of Oklahoma—in which traffic offenses similarly account for a large portion of failure to pay cases—suggests that court debtors risk jail for even comparatively small amounts of debt. In Oklahoma, the median court costs in traffic cases where a failure to pay warrant was issued was around $500.

A Better System

These findings paint a troubling picture of a system in which tens of thousands of people are jailed each year for unpaid court debts, often stemming from minor offenses. The financial and social costs of this practice are substantial, extending far beyond jail itself. Many of the individuals we spoke to found themselves scrambling to make arrangements for their jobs and children after being arrested for unpaid court debts years after the original offense. The cost is not only heavy for them: the public at large expends considerable resources to incarcerate these individuals for unpaid debts that will not be recouped. Policymakers must consider alternative approaches for handling unpaid court debt, from public service and other alternative sentencing programs, to reducing fines associated with petty offenses, to implementing more equitable income-based fines. Efforts to limit the practice of jailing court debtors in states like Colorado and Texas show that reform is possible. Without central data collection, much remains unclear about debt imprisonment. We nevertheless hope that this data integration effort—which would never have been possible without the dedicated effort of the many people who worked on this project with me—will serve as a resource for journalists, advocates, and policymakers are working to reduce the social and financial costs of debt imprisonment.

(Many thanks to my co-authors, Phoebe Barghouty, Sarah Vicol, Cheryl Phillips, and Sharad Goel; as well as Joshua Grossman, James Hamilton, Jane Lee, Emily Lemmerman, Joe Nudell, and Keniel Yao for their contributions to the thankless tasks of investigation, data collection, and data cleaning.)

-

James Wilson (1742–1798) was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, and an associate justice of the Supreme Court. He was also a land speculator who was twice imprisoned for unpaid debts in 1797. See: Ewald, William. “James Wilson and the Drafting of the Constitution.” U. Pa. J. Const. L. 10 (2007): 901. ↩

-

Mill, John. Principles of Political Economy (Ashley ed.). Longmans, Green, and Company, 1848. Chapter 9, Section 8. ↩

-

Coleman, Peter J. Debtors and creditors in America: insolvency, imprisonment for debt, and bankruptcy, 1607-1900. Beard Books, 1999. ↩

-

Except in Rhode Island; see Rhode Island Family Life Center. “Court Debt and Related Incarceration in Rhode Island from 2005 through 2007.” (2008). ↩

-

For full details of how we coded failure to pay, see the paper. ↩

-

Similar considerations apply to the other estimates in this post. Full details for all the estimates are given in the paper and the reproduction materials. ↩